Sheffield DA Winter Walk 2026

Graves Park: Layers of Time in Sheffield’s Green Heart

This walk through Graves Park is not simply a circuit of paths. It is a passage through layered time: prehistoric geology, medieval estate management, early industrial change, Victorian transport routes, and a deliberate 20th-century act of preservation that still shapes Sheffield’s quality of life today. Read on the find out more about the route of our walk.

At roughly 248 acres, Graves Park is Sheffield’s largest park. What makes it exceptional is not only its size, but the fact that so much of its earlier structure remains legible in the landscape. Fields, woods, ponds, and routes still follow patterns laid down centuries ago.

THE PARK AS A GIFT, NOT AN ACCIDENT

The park exists because John George Graves, a Sheffield businessman and alderman, deliberately chose to acquire land on the southern edge of the city and give it to Sheffield Corporation between the 1920s and 1930s. His stated intention was to protect ancient woodland, open land, and historic features from housing development, ensuring permanent public access.

This was not an act of beautification alone. It was an act of civic foresight. At a time when Sheffield was expanding rapidly, Graves understood that once land is built on, it is almost never reclaimed. Graves Park represents an early recognition of the social, environmental, and psychological value of green space.

BUNTING NOOK: WHERE FOLKLORE ATTACHES ITSELF TO PLACE

Walking along Bunting Nook, the park’s northern edge, you encounter a landscape that feels enclosed and transitional. It is here that Sheffield’s folklore thrives. Stories of apparitions, strange sounds, and unexplained encounters have circulated locally for generations.

These accounts are not historical evidence in the academic sense, but they are culturally significant. Folklore tends to gather in liminal spaces: boundaries between park and road, light and shade, town and countryside. Bunting Nook is precisely such a place. Whether believed or not, the stories reflect how people emotionally register the landscape.

NORTON: A VILLAGE ABSORBED, NOT ERASED

Beyond Bunting Nook stands St James’ Church, Norton, the centre of what was once the independent village of Norton. Norton is recorded in the Domesday Book and has evidence of continuous settlement for over a thousand years.

The church itself has medieval origins and remains a focal point for local identity. Norton’s most famous son, Sir Francis Chantrey, was born here in 1781. Chantrey became one of Britain’s leading sculptors, and his association links this quiet edge-of-Sheffield village to national cultural history.

Norton’s survival as a recognisable place, even after being absorbed into Sheffield’s boundary, illustrates how villages do not disappear when cities grow; they are layered into them.

St. James’ Church, Norton

THE NORTON ESTATE: MEDIEVAL LAND MANAGEMENT

Re-entering Graves Park, you step onto land once known as Norton Park, part of a medieval estate with documented references dating back to the early 11th century. This was not wilderness. It was actively managed land. Evidence suggests:

Deer parks used for hunting and status

Fishponds dug for food security

Open fields and enclosed pastures

Woodland managed for timber and fuel

Many of the park’s present-day shapes reflect these uses. Subtle ridges, boundaries, and alignments persist because later landowners worked with the existing landscape rather than erasing it.

RARE BREEDS AND AGRICULTURAL CONTINUITY

The Animal Farm and Rare Breeds Centre sits naturally within this long agricultural narrative. The presence of Highland cattle, Jacob sheep, alpacas, pigs, donkeys, and goats is not merely decorative. It reflects a conscious effort to preserve traditional livestock genetics and reconnect urban populations with food and farming heritage.

For children especially, this is often their most direct encounter with animals that shaped rural life for centuries. For adults, it reinforces the idea that Graves Park is not just recreational land, but a continuation of managed countryside within the city.

WATER AS INFRASTRUCTURE: THE THREE PONDS

The three ponds are among the park’s oldest features. Originally medieval fishponds, they later served multiple purposes:

Livestock watering

Ice skating in winter

Ornamental boating during the estate period

Today, they form a connected hydrological system that supports wildlife, fishing, and a diverse natural ecosystem of flora and fauna. Water flows between them before cascading beneath the footpath in a small waterfall, creating conditions ideal for mosses, liverworts, and shade-loving plants.

These ponds are a reminder that water management has always been central to successful landscapes.

The Waterfall, Graves Park, Sheffield

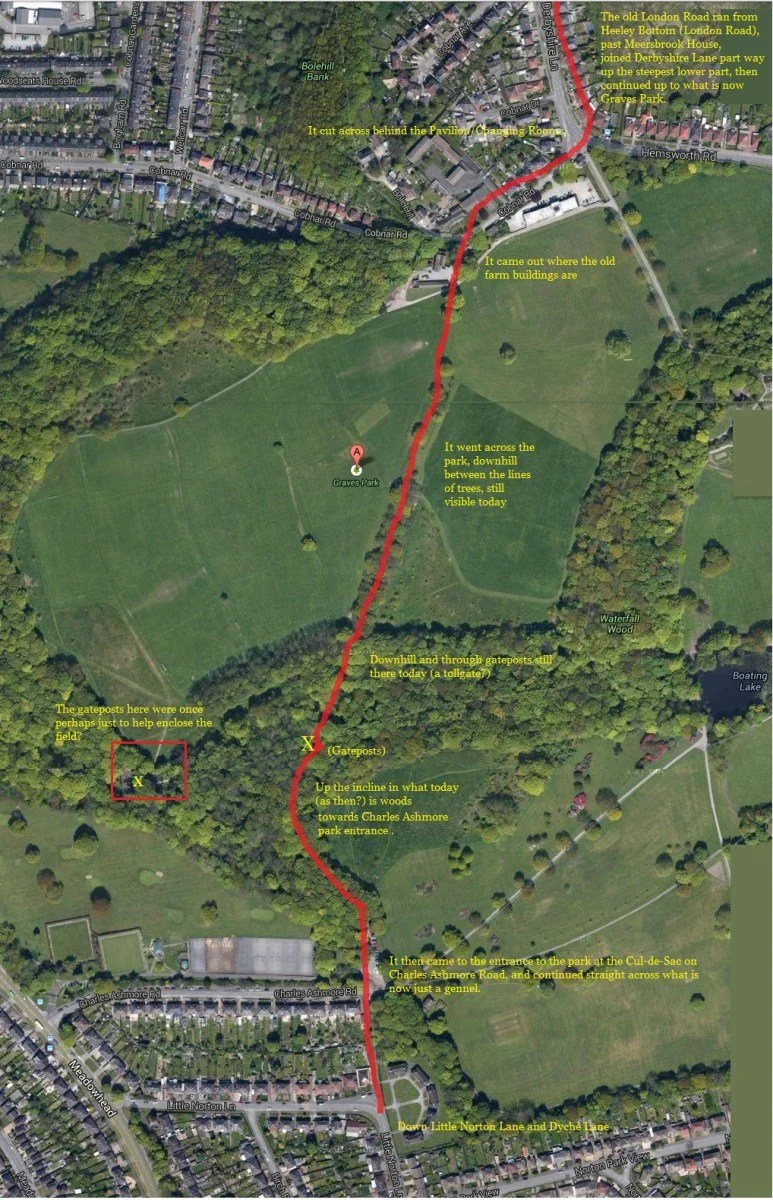

THE OLD LONDON TURNPIKE: MOVEMENT ETCHED INTO EARTH

As the walk briefly follows the line of the Old London Turnpike Road, the landscape reveals the physical consequences of long-term use. Before the modern A61 was established through Woodseats and Meadowhead in the 18th century, this route carried carts, horses, mail, and people heading south.

The sunken nature of the track is not accidental. It is the product of centuries of erosion caused by traffic, leaving a hollow way that quite literally records movement through time.

Route of the ancient Sheffield to London Turnpike, Graves Park, Sheffield.

(Image credit, John E Boy, Sheffield history Group, February 20, 2014)

COBNAR WOOD, BOLEHILL AND EARLY INDUSTRY

Cobnar Wood introduces a different layer of history. The name Bolehill likely relates to early lead processing or smelting, where “bole” refers to primitive furnaces. Quarrying and extraction have left subtle marks in the woodland, reminders that even apparently natural spaces were once economically productive.

This dual identity - industrial and pastoral - runs throughout Graves Park.

WOODSEATS: SHIFTING BOUNDARIES

Descending Cobnar Road brings the walk into Woodseats, once an independent settlement and historically part of Derbyshire. Boundary changes in 1901 incorporated Woodseats, Norton, and Beauchief into Sheffield.

These administrative changes altered governance but did not erase local character. Graves Park sits at the meeting point of multiple historic identities.

THE RAVINE AND THE COLD STREAM: DEEP TIME MADE VISIBLE

One of the park’s most powerful features is The Ravine, carved by the Cold Stream over thousands of years. This steep-sided valley predates every human intervention seen on the walk so far.

In the 1920s, rather than flattening or hiding it, park designers enhanced the ravine with paths and crossings. The result is a place where geology, ecology, and design coexist.

Here, sandstone outcrops associated with Sheffield’s Coal Measures are visible. Ferns, mosses, fungi, and insects thrive in the cool, damp microclimate. Sound is softened. Air feels cleaner. This is one of the clearest examples of why Graves Park matters not only historically, but psychologically.

The Cold Stream cascading down The Ravine, Graves park, Sheffield.

WATERFALL WOOD AND THE DESIGNED PARK

Climbing through Waterfall Wood, the walk transitions from wild valley to designed landscape. The Rose Garden Café, built in the late 1920s, and the formal rose gardens planted in the 1930s represent the park’s final transformation into a civic space intended for rest, leisure, and social connection.

This is where Graves Park’s identity becomes clearest: not wilderness, not museum, but a carefully balanced public landscape.

WHY GRAVES PARK STILL MATTERS

Graves Park is valuable precisely because it is layered. It holds:

Over a thousand years of land use

Rare surviving medieval features

Industrial traces

Designed 20th-century parkland

Living ecosystems

Community use across generations

None of this survives by chance. It exists because land was protected, valued, and shared. Walking the park with context reveals it not just as a place to pass through, but as a civic inheritance that continues to reward care and attention.